"A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies"

Philippa Gregory ~ The Kingmaker's daughter, Ann Neville

This is another vivid portrayal of Plantagenet Britain, and the political intrigues and personal tragedies bound up in the manoeuvring for power and the expectations of children tutored by ambitious parents.

At first sight Richard appears to be the only character genuinely not out for himself constantly, and able to look beyond his personal ambitions. Will he descend to the lowest common denominator? Will his and Anne's love story remain a happy one throughout their marriage?

It seems that the documented evidence was fairly thin on the ground, and for a historian Philippa Gregory had quite a lot of scope in this volume to turn the story and its motivations as she would. Occasionally this led me to feel that there were some slightly false notes - perhaps the emotions and motivations of the characters were just insufficiently delineated for my personal taste.

Nevertheless on the whole a gripping read, and a clear depiction of a period of troubled British history.

Death with interruptions ~ José Saramago

This was a very strange book. I spent over half the book being irritated by the paragraph long sentences, the lack of punctuation and the lack of character. The entire book really only draws two characters with any degree of personality, and one of those not until well into the second half of the book. If I were not accustomed to persevering with books (there must have been something that made a publisher take it on, as my librarian parents used to tell me when I was a child).... Old habits are hard to break, and even in these days of self-publishing, which can lead to some very iffy books, I tend to say "I've started so I'll finish."

In the end I was glad I did persevere, although it was really only the end of the book that I enjoyed. Much of the rest was abstract, almost theoretical and not my cup of tea. It was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature however, which also made me continue to struggle with it. Because of the effort I had to put in it was not a quick read. Would I reread it another time? Probably not, but I can see finally that it did have some literary merit.

Now I may be doing it a disservice. In its original, which I assume was Portuguese, I suspect the long sentences are more easily comprehended as I have come across that trait before. I cannot judge the translation, though, only the impression the book made upon me.

Rabbit-proof fence by Doris Pilkington

This sounded like an amazing true story of the journey three Aboriginal girls, removed from their families, but unfortunately the blurb on the back of the book did not seem to tally with the story: "After regular stays in solitary confinement, the three girls - scared and homesick - planned and executed a daring escape.."

In the book the escape does not feature until chapter 8 out of 9, and the girls only arrive at the camp in chapter 7!

The book is interesting and valuable in that it sets out the events that were replicated across Australia in 1931, written from the Aboriginal point of view. However the escape, told as the writer's mother had told it to her, lacks details of distance and is blurry about some of the events, shrouded as the telling was in the mists of time. The lack of measurements is because these are not used in the Aboriginal tongues so were not available, only some names of settlements and farms are given.

In summary it is a valuable book, but not as enthralling as I had hoped or expected.

1

1

The boy with the bronze axe Kathleen Fidler

I got this little children's book from Amazon, as part of my on-going research into the neolithic village at Skara Brae in the Orkneys, for the novel I am writing. It was written by a Scottish woman who became a headmistress in Leicestershire and began writing stories for her own children. Born in 1890, she died in 1980 having become a fairly prolific author of novels and children's books.

The story it tells is compelling, and begins by setting the scene well, establishing the feel of life in those times for a clan living out a precarious existence on an island in the Orkneys, and having to adapt to change with the arrival of a boy who has a bronze axe and a need to explore and travel.

The premise for Skara Brae is very different from my own, and I feel does not account for the sophisticated construction of Maeshowe. However she suggests that the clan is in decline having lost the knowledge of their ancestors, which is a reasonable supposition.

What a shame that the author did not live to see the further finds south of the Skara Brae settlement. However, it is very well written as a story for children of about eight upwards- suggested age is 9+, and certainly would appeal to both boys and girls of top Junior school age (10-11), and should be within their vocabulary range, whilst she does not hesitate to use correct words for things mentioned.

The book contains suspense, adventure, peril, and ends on an optimistic forward-looking note.

Sky Burial:An epic love story of Tibet by Xinran Xiu

This slim volume tells the story of a Chinese woman, married only one hundred days whose husband is declared dead when he is posted to Tibet with the Chinese Liberation Army. No other details are forthcoming, and so Shu Wen sets off to Tibet, as a medic. joining the army there, so that she can find out what has happened to her husband. The book follows her years in Tibet, and her search for information about her husband, and perhaps to find him alive still. It is charmingly told and gives one a real insight into the empty wastes of much of Tibet, the way of life of the nomadic herders, the strong religious aura of the people, and the stark differences from Chinese culture.

There are passages that touch on the reasons for the conflict and the differences between the perceptions of it within China and those that are evident when she is in Tibet and surrounded by Tibetans.

I will certainly look out for other of Xinran's tales of strong Chinese women.

1

1

12

12

Awakenings

I have read about half of this book to date. I picked it up not realising it was non-fiction, but it is a fascinating and sad account of people who had spent decades in trance-like states the results of a mystery illness, Encephalitis lethargica. That there have been outbreaks of this possibly viral illness in various places from the earliest reported times of history makes it quite extraordinary that so little was known about it. Outbreaks seem to hit individuals totally at random - one person in a school of four hundred, single members of families, and very often it has gone undiagnosed. The person will often be described as frozen, retarded, psychotic.

The symptoms are very variable and often quite diametrically opposed in type from tics that cause lightning fast repeated movements or speech to ones that result in the patient freezing mid-action for hours, or months at a time.

When roused from this state by the use of a 'wonder drug' the reactions again were varied and unpredictable and the side effects and reactions to the dose seem also to have been unpredictable and sometimes more terrible than the state of suspended animation. The patients' reports during these awakenings are so like stories like Alice in Wonderland and the Sleeping Beauty that I cannot but think that the authors of such stories had come into contact with people suffering from this condition.

The stories are sad, from those who found the loss of all their adult years unbearable, to those who accepted it but then had to be taken off the drug which released them from it because of terrible adverse reactions which plunged them into a nightmare existence.

Each case study tells a different, very personal story, each a tragedy of lost life. I have read the case studies and am now onto the final summary, but I am finding it tough reading, littered as it is with medical terms and vocabulary with which I am not familiar, and which in many cases are not to be found in the glossary either.

I have found it particularly gruelling wading through the notes of Sacks' conclusions at the end of the book. Whereas the case notes held a fascination in opening a door onto the very varied, and dream/nightmare qualities of the worlds these post-encephalitic patients inhabited, the notes and summaries did not really add anything for me and were couched in psychiatric and medical terms which made them difficult reading.

The book has given me a loathing for footnotes, some of which in this slim volume took up 80 to 90% of five or six pages. They disrupted my reading and were awkward. To my mind it has confirmed the feeling that if it needs saying it should be in the text, if not, omit it altogether. Many of these notes may be due to the revision of the book by him in 1976 (orig. released 1973), but he would have been better just to rewrite it, or to add new chapters after the original book's end.

I wonder if I have been unfair in my judgement of methods and treatments now 41 years plus in the past. However I worked in a huge mental hospital for several months in the early 1960s and I already condemned and spoke up about some of the care and treatment offered there. I am sure my outrage now is merely a product of my character and not of the times we live in.

A sad book about devastated lives merely the tip of an iceberg since thousands were affected.

6

6

The Prisoner of Zenda and Rupert of Hentzau

| I found we had the Heron hard cover edition of these two titles and I believe I read the Prisoner of Zenda when I was in my teens. I picked it up to read both parts, partly because I remember my mother telling me that my paternal grandmother was reading this book whilst she was expecting my father and that was how he got his name. I was surprised to find that she had chosen the villain of the piece's name as her favourite. Perhaps the wicked streak goes deep in our family! I did find the whole book very predictable but quite enjoyable nevertheless, despite it being rather over the top in its romanticism. Not the sort of books I will read again however. The nicest thing about it is the tooled cover. |

Brasyl by Ian McDonald

My younger son gave me this book to read. It irritated me with lazy grammatical faults and sloppy writing - repeated words in sentences and short-hand sentence construction that often had me reading a sentence several times to make sense of it.

Written in alternating sections dates 2006, 2032 and 1732 it took a long time before I remembered which characters were from 2006 and which from 2032. I preferred the slower style and descriptive passages in the 1732 chapters, and found the 2032 parts the most annoying, having many things have already proved out of date when we are only six years past the publication date of the book.

Ian McDonald can construct plot and there were parts of the action which were exciting and encouraged one to read on, but on the whole I think I shall not go looking for more of his books, there being ones I far prefer to spend my time on, out there.

The Praise Singer by Mary Renault

Revisited over the holiday period. Last read when I was a teenager, many moons ago. I loved this book even more this time, and found much truth in its pages. It is a skillful blend of careful and detailed research into the period (6th century BC), fictional invention and brilliant writing.

There is a current emphasis on immediately grabbing a reader with dramatic action at the start of a novel, and maintaining a frantic pace and much drama throughout. If that is what you want this will not be your cup of tea, but it is a book that takes one into the atmosphere and the life of the bard Simonides, renown for his ugliness and his beautiful verse and music. The times and the historical figures are evoked and spring to life. Simonides is not a saint, he is flawed and fallible and one can see what will happen before he does at times even if one does not know the history, but his account is a personal and three dimensional one that reverberates with the music and words of the time.

I have a young friend who prefers reading Homer to novels, and shall see if I can persuade her to read this. I guarantee it will start her on a reading life she has not known before.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

Well written and researched this book addresses the issue of ownership of body parts that have been used for medical analysis or just taken as if that is the case, but kept and used profitably without the knowledge of the donor or the family of the donor.

I particularly found the end chapter about research and the issues it has raised interesting and well thought out. I got the book intending it for my daughter-in-law who is a scientific researcher, but ended up reading and recommending it for general consumption. It also made me glad to be in a country where medicine prescribed is free and treatment is available to all free at the point of use (paid for by contributions taken through taxation of those in work or on pensions over a minimum amount). We complain about the shortcomings of our system, but it is far more even-handed and available to the vulnerable and needy than that prevalent in the US. For that I am grateful. It made me wonder about the issue of agreement for use of cells etc. here, and that I am unsure about. Blood we give free and voluntarily, and spare parts too, both before and after death, but whether cells and samples taken during treatment could be sold as in the cases cited in this book, I do not know, but intend to find out. As with the daughter of HL who is the main focus of the interviews Skloot conducted, my main interest would be that permission should be given, and information given to donors, not that financial reward should be sought. But then in the UK we don't pay when treated (except for dentistry and opticians) so why should we be paid either?

1

1

2

2

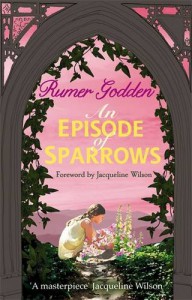

An Episode of Sparrows by Rumer Godden

Since my computer is misbehaving and we had no power over the Christmas period, the weather was atrocious and Mark was ill, but we had lights, I spent a lot of time reading. I decided to revisit books I read in my teens. I suspect I read this one when I was about twelve first, and remembered it with affection, although as usual with no recollection of the contents.

I agree almost completely with Andrew Smith's review and will not rewrite it in less good terms. However I found the ending too unlikely now - [spoiler alert!]it seems more likely the family would get such a will overturned. [end of spoiler]

Perhaps age has made a cynic of me! Lovejoy is a delight still and there are touching moments, but unlike one reviewer I cannot see this as having anything in common with chicklit! A delightful step back into my youth. More to come...

An Instance of the fingerpost by Iain Pears

This is a very clever book, written from four different perspectives, of participants in the events, but it left me dissatisfied, as I felt no personal attraction to any of the four characters. When I started reading the second account I found it pretty confusing, as it seemed initially to be talking about an entirely different set of events.

If you are the sort of reader who delights in untangling events and working out 'who dunnit' then you may well enjoy this period crime drama, set in the reign of Charles the second, with all the political intrigues, complexities of religious dissent and backroom dealings that followed the Commonwealth era. It is not, to my mind, a book where the author attempts to involve you emotionally with his characters, and I am afraid that is what I seek in fiction.

What the author does achieve supremely well is to recreate the period with detail and well-researched facts - may of the protagonists - political, society, medical, scientific figures - are real historical characters, and short bios of them are given at the end of the book.

1

1